James Blish was a popular science fiction writer and critic who began his literary career while still in his mid-teens. Not yet out of high school, Blish created his own science fiction fanzine, and shortly thereafter became an early member of the Futurians, a society of science fiction fans, many of whom went on to become well-known writers and editors. From the ’40s to the ’70s, Blish submitted a slew of fascinating tales to a variety of pulp magazines, including Future, Astounding Science Fiction, Galaxy Science Fiction, The Magazine of Science Fiction and Fantasy, and Worlds of If, just to name a handful. Although Blish’s most widely recognized contribution to the science fiction genre may be his novelizations of the original 1960s Star Trek episodes (to which his talented wife Judith Lawrence contributed), his magnum opus is undoubtedly the numerous “Okie” tales written over the span of a decade and merged together into the four-volume series known as Cities in Flight.

To give you some background, it was in 1991, when I entered Junior High School—a brave new world indeed—that I first discovered James Blish. For it was then, to celebrate Star Trek’s 25th anniversary, that Blish’s adaptations were compiled in three thick paperback volumes, each containing a full season’s worth of episodes. As I recall, the first book, which collected season one, was purple; the second was red, and the third was blue. I purchased the first two volumes at SmithBooks in the summer of 1992. I enjoyed them immensely; I read and reread them repeatedly, never tiring of them. (I finally managed to snag the third—in pristine condition, to my delight—at a used bookstore a decade later.) And the extra insights and background exposition by Blish, however perfunctory or limited (which in many respects, they were) made me feel as though I actually knew the characters personally.

After reading these novelizations in the early ‘90s, I set out to find other science fiction works by Blish. Recognizing that he was an author from before my time, and a prolific one, I decided that my best bet would be to check out used bookstores, which were more than likely to carry at least a modest selection of his books. I was right, as it turned out, and took the opportunity to pick up a couple of other novels by Blish: VOR (a story of the first time an alien being crash lands on Earth, and then insists that it wishes to die) and Jack of Eagles (a tale about an ordinary American man who discovers he has enhanced psionic powers). Both of these relatively short novels are intriguing in their own right. It was also at a used bookstore that I first came across the Cities in Flight omnibus—although I confess that upon initial perusal it looked very formidable to my fourteen-year-old eyes.

ABOUT JAMES BLISH

James Blish, born in 1921 in East Orange, New Jersey, was a gifted writer of science fiction and fantasy. As mentioned above, his interest in these genres began early. At the age of fifteen, Blish began to publish The Planeteer, a monthly science fiction fanzine he both edited and contributed to from November 1935 to April 1936. For each issue, Blish penned a science fiction tale: Neptunian Refuge (Nov. 1935); Mad Vision (Dec. 1935); Pursuit into Nowhere (Jan. 1936); Threat from Copernicus (Feb. 1936); Trail of the Comet (Mar. 1936); and Bat-Shadow Shroud (Apr. 1936). In the late 1930s, Blish joined the Futurians, a body of sci-fi writers and editors based in New York City who significantly influenced the development of the sci-fi genre between 1937 and 1945. Other members included sci-fi giants Isaac Asimov and Frederik Pohl.

James Blish, born in 1921 in East Orange, New Jersey, was a gifted writer of science fiction and fantasy. As mentioned above, his interest in these genres began early. At the age of fifteen, Blish began to publish The Planeteer, a monthly science fiction fanzine he both edited and contributed to from November 1935 to April 1936. For each issue, Blish penned a science fiction tale: Neptunian Refuge (Nov. 1935); Mad Vision (Dec. 1935); Pursuit into Nowhere (Jan. 1936); Threat from Copernicus (Feb. 1936); Trail of the Comet (Mar. 1936); and Bat-Shadow Shroud (Apr. 1936). In the late 1930s, Blish joined the Futurians, a body of sci-fi writers and editors based in New York City who significantly influenced the development of the sci-fi genre between 1937 and 1945. Other members included sci-fi giants Isaac Asimov and Frederik Pohl.

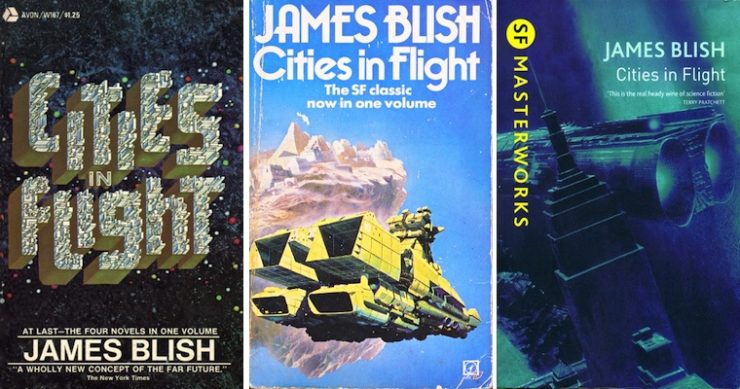

Blish’s first published story, Emergency Refueling, appeared in the March 1940 issue of Super Science Stories, a pulp magazine. Throughout the 1940s, such magazines were the main venue in which his stories saw print. It was between 1950 and 1962, however, that Blish published his crowning achievement, the Cities in Flight tetralogy. In 1959, Blish won the Hugo Award for Best Novel for A Case of Conscience, and was nominated in 1970 for We All Die Naked. He was also nominated for the Nebula Award on three occasions: in 1965 for The Shipwrecked Hotel, in 1968 for Black Easter, and 1970 for A Style in Treason. Also in 1970, Avon Books collected the four Cities in Flight novels and rereleased them together, for the first time, in one hefty volume.

The very commercially successful Star Trek novelizations of the original 1960s television episodes that remain Blish’s best-known work were released over a ten-year period—from 1967 to 1977—in twelve slim volumes, each with multiple printings to accommodate the widespread demand. In addition to these popular, highly-readable short stories, he also wrote the first original adult Star Trek novel, Spock Must Die!, which was released in February 1970 by Bantam Books, one year after the original television series was—to the dismay of loyal viewers—canceled by NBC. And although it was not widely known to the general public, Blish also used the pseudonym William Atheling, Jr. to write critical science fiction articles, as well.

As a final note, I thought it apt to include an interesting fact about Blish: In 1952, he originated the term “gas giant” to describe immense gaseous planets when he altered the descriptive text of his 1941 tale Solar Plexus. The relevant passage reads: “… a magnetic field of some strength nearby, one that didn’t belong to the invisible gas giant revolving half a million miles away.”

THE EPIC: CITIES IN FLIGHT

Cities in Flight, Blish’s galaxy-spanning masterpiece, was initially published as four separate books well over a half-century ago. It should be noted, however, that the four original books were not written in sequential order. According to James Blish, “The volumes were written roughly in the order III, I, IV, [and] II over a period of fifteen years…”

The first novel, They Shall Have Stars, was published in 1956; the second, A Life for the Stars, was published in 1962; the third, Earthman, Come Home, was published in 1955; and the fourth, The Triumph of Time, was published in 1958. Finally, in 1970 the “Okie” novels, as they were dubbed thereafter, were skillfully woven into a single epic-length tale and published in an omnibus edition as Cities in Flight.

The stories which compose the Cities in Flight saga were inspired by the Great Migration of “Okies” (a colloquial and unflattering appellation for rural Americans from Oklahoma) to California in the 1930s due to the Dust Bowl. The latter is a term referring to the intense dust storms—so-called “black blizzards”—that devastated farmland in the Great Plains during the Great Depression. And to some extent, Blish was influenced by Oswald Spengler’s major philosophical work, The Decline of the West, which posited that history is not divided into epochal segments but cultures—Egyptian, Chinese, Indian, etc.—each lasting approximately two millenia. These cultures, Spengler averred, were like living beings, who thrive for a time and then gradually wither away.

Cities in Flight tells the story of the Okies, albeit in a futuristic context. These Earthmen and women are migrants who voyage through space while living in enormous, detached cities capable of interstellar flight. The purpose of these nomadic folk is rather prosaic—they are driven to search for work and a viable lifestyle due to the worldwide economic stagnation. Powerful anti-gravity machines known as “spindizzies,” built into the bottommost layer of these city-structures, propel them through space at post-light speed. The result is that the cities are self-contained; oxygen is trapped inside an airtight bubble of sorts, which harmful cosmic material cannot penetrate.

Blish’s space opera is tremendous in its scope. The full saga unfolds over several thousand years, features many ingenious technological marvels, and stars dozens of key protagonists and many alien races who are confronted by ongoing predicaments that they must overcome through ingenuity and perseverance. The story vividly conveys both Blish’s political leanings and his disdain for the present condition of life in the West. For instance, Blish’s loathing of McCarthyism—which was then at full steam—is evident, and in his dystopian vision, the FBI has evolved into a repressive, Gestapo-like organization. Politically, the Soviet system and the Cold War still exist, at least in the first installment, although the Western government has done away with so many personal freedoms as to render the Western social order a mirror of its Soviet counterpart.

They Shall Have Stars is the first of the four novels. Here, the far reaches of our own solar system have been fully explored. However, mankind’s desire to proceed even further into the unknown is made possible through two vital discoveries: one, anti-aging drugs which allow the user to prevent senescence; and two, anti-gravity devices that facilitate galactic travel. Hundreds of years have elapsed by the time of A Life for the Stars, the second installment, and mankind has developed sufficiently advanced technology to permit Earth’s largest cities to break away from the Earth itself and set off into space. The third novel, Earthman, Come Home, is related from the viewpoint of centuries-old New York mayor John Amalfi. The societal changes resulting from centuries in galactic transit have not been favorable; by this time, the space-roaming cities have regressed to a savage, chaotic state, and these renegade societies now endanger other enlightened offworld civilizations.

The last of the four novels, The Triumph of Time, continues from Amalfi’s perspective. The New York city-in-flight is now passing through the Greater Magellanic Cloud (a dwarf galaxy some fifty kiloparsecs from the Milky Way), although a new threat of galactic proportions is impending: a cataclysmic collision of matter and anti-matter that will destroy the universe. This is known as the Big Crunch, a theoretical scenario in which it is hypothesized that the universe will eventually contract and collapse in on itself due to extraordinarily high density and cosmic temperatures—the reverse of the Big Bang. If interpreted in religious terms, the ending parallels the beginning of the Old Testament’s Book of Genesis—or rather, presents its inescapable opposite.

Truth be told, Blish’s space epic is a rather pessimistic conception of mankind’s future. And although it is undeniably dated by today’s standards—some amusing references to obsolete technology are made (slide rules, vacuum tubes, etc.)— present-day readers will still appreciate the quality of the literature and, as a benchmark example of hard science fiction, find it a memorable read.

A FINAL RECOMMENDATION

For a generous sample of James Blish’s finest work spanning a three decade-long career, I personally recommend The Best of James Blish (1979), which I recently acquired online. It is a carefully selected collection of short stories, novelettes, and novellas, which in the opinion of some readers, including my own, tend to surpass some of his lengthier works. For convenience, here is a list of its contents: Science Fiction the Hard Way (Introduction by Robert A. W. Lowndes); Citadel of Thought, 1941; The Box, 1949; There Shall Be No Darkness, 1950; Surface Tension, 1956 (revision from Sunken Universe, 1942 and Surface Tension, 1952);Testament of Andros, 1953; Common Time, 1953; Beep, 1954; A Work of Art, 1956; This Earth of Hours, 1959;The Oath, 1960; How Beautiful with Banners, 1966; A Style in Treason, 1970 (expansion from A Hero’s Life, 1966); and Probapossible Prolegomena to Ideareal History (Afterward by William Atheling, Jr., 1978).

Thomas Xavier Ferenczi is a man of diverse background. Born in Edmonton, Alberta, he has studied management, pharmacology, and law. As an author, he has written a science fiction screenplay, Extraterrestrial, and his most recent project is a techno-thriller, Conspiracy. He is also a writer in many other genres, including legal and historical non-fiction. He has a particular affinity for the science fiction tales of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A bookworm, he can often be found in a coffeeshop, diner, or pub with his nose buried deep in a novel or textbook. He currently resides in Western Canada.